Across focus group participants, there are mixed views regarding the effect of Copilot on skills development. Two focus group participants noted that they were concerned that Copilot may result in APS staff not needing to develop and maintain their subject matter expertise as they can instead rely on Copilot. They also commented that a reliance on Copilot for writing could decrease participants’ writing skills and ability to construct logical arguments.

However, 2 focus group participants remarked that reductions in competencies in some areas is acceptable as generative AI will fundamentally change the skills that are needed in the APS. For example, one focus group participant commented that taking notes will become less important whereas critically assessing output will become more relevant.

The concerns around potential skill decay suggest that there should be ongoing analysis into key workplace competencies as generative AI becomes increasingly incorporated in the APS. This analysis could also identify how to best support skill development in these competencies.

There are concerns related to vendor lock-in.

Vendor lock-in refers to a situation where a customer becomes overly dependent on a particular vendor's products or services, making it difficult, costly or impractical to switch to another vendor or solution. Vendor lock-in can happen through proprietary technologies, incompatible data formats, restrictive contracts, high switching costs, complex integrations and specialised knowledge requirements.

To use Copilot, an organisation must have a Microsoft365 licence that allows them to use a range of Microsoft products. Two focus group participants noted that Copilot’s easy integration with existing Microsoft licences could mean they are likely to remain with Copilot even if better products become available and that this could reduce competition.

The potential for Copilot to result in vendor lock-in suggests that agencies should look to monitor alternative generative AI options that may better suit their needs. This is particularly pertinent for products that may be more effective but also more difficult to implement.

Generative AI use could increase the APS’s environmental footprint.

Most generative AI products have a high carbon footprint. This occurs as AI models require vast amounts of energy to power their data centres that train generative AI models and to power each individual request. Some photo-generation generative AI tools use as much energy to produce an image as it takes to fully charge a smartphone (Luccioni et al. 2024).

The APS Net Zero Emissions by 2030 outlines the APS’s commitment to achieve net zero in government operations by 2030. One focus group participant was concerned that Copilot will lead to an increase in the APS’s carbon footprint as more licences are distributed and adoption continues.

This suggests that future uptake should also consider the carbon footprint of potential models, in line with agencies’ own targets around reducing their footprint.

Reference

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (2024) ‘Copilot for Microsoft 365; Data and Insights’, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT, 8

- Department of Home Affairs, ‘Copilot Hackathon’, Department of Home Affairs, Canberra, ACT, 2024, 10

- Luccioni S, Jernite Y and Strubell E (2024) ‘Power Hungry Processing: Watts Driving the Cost of AI Deployment?’, FAccT ’24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.16863, (accessed 3 September 2024).

A.1 Overview of the Microsoft 365 Copilot trial

The whole-of-government trial of Copilot was conducted to examine the safe and responsible use of AI in the Australian Public Service (APS).

On 16 November 2023, the Australian Government announced a 6-month whole-of-government trial of Microsoft 365 Copilot.

The purpose of the trial was to explore the safe, responsible, and innovative use of generative AI by the APS. The trial aimed to uplift capability across the APS and determine whether Copilot, as an example of generative AI:

- could be implemented in a safe and responsible way across the government

- posed benefits and challenges/consequences in the short and longer term

- faced barriers to broader adoption that may require changes to how the APS delivers on its work.

The trial provided a controlled setting for APS staff to explore new ways to innovate with generative AI. It also served as a useful case study that will inform the government’s understanding of the potential benefits and challenges associated with the implementation of generative AI.

The trial was co-ordinated by the DTA, with support from the AI in Government Taskforce, and ran from January to June 2024. The DTA distributed over 7,769 Copilot licenses across almost 60 participating agencies. The trial was non-randomised – agencies and individuals volunteered to participate. A full list of agencies that participated can be seen in A full list of agencies that participated can be seen in Appendix C.1 Overall participation.

The trial focused solely on Copilot – a generative-AI enabled intelligent assistant embedded within the Microsoft 365 suite.

Microsoft 365 Copilot, launched by Microsoft in November 2023, is a generative AI tool that interfaces directly with Microsoft applications such as Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, Teams and more. Copilot uses a combination of large language models (LLMs) to ‘understand, summarise, predict and generate content’. While Copilot continues to evolve, its functionalities in the trial broadly were:

- Content generation – drafting documents, emails and PowerPoint presentations based on user prompts,

- Summarisation and theming – providing an overview of meetings, documents and email threads, and identifying key messages,

- Task management - suggesting follow up actions and next steps from meetings, documents and emails

- Data analysis – creating formulas, analysing data sets and producing visualisations.

Copilot produces outputs by incorporating user and organisational data – or if configured by users, to also source Internet content – to produce an output. The ability to use organisational data is due to Microsoft Graph – a service that connects, integrates and provides access to data stored across Microsoft 365.

Microsoft Graph ensures that Copilot complies with an agency’s existing Copilot security and privacy settings and provides contextual awareness to outputs by drawing on information from emails, chats, documents and meeting transcripts which the user has access to.

Microsoft also offers a free web version of Copilot. Although not the subject of the evaluation, the AI-assisted chat service and web search (formerly named Bing Chat) offers similar functionality to Copilot, albeit not embedded into applications and does not utilise internal data and information.

Architecture and data flow of Microsoft 365 Copilot

- The user’s prompts are sent to Copilot.

- Copilot accesses Microsoft Graph and, optionally, other web services for grounding. (Microsoft Graph is an API that provides access to the user’s context and content, including emails, files, meetings, chats, calendars and contacts.)

- Copilot sends a modified prompt to the LLM.

- The LLM processes the prompt and sends a response back to Copilot.

- Copilot accesses the Microsoft Graph to ensure that data handling adheres to necessary compliance and Purview standards.

More information about Microsoft 365 Copilot’s architecture can be found via Microsoft Learn at https://learn.microsoft.com/en-au/copilot/microsoft-365/microsoft-365-copilot-overview

Copilot was deemed a suitable proxy of generative AI for the purposes of the trial.

The DTA selected Copilot to be trialled as a proxy for generative AI. Copilot was chosen for 3 main reasons:

Copilot offered comparable features to other off-the-shelf generative AI products.

Copilot is powered by the same LLMs and possesses similar functionality to other publicly available generative AI tools.

Copilot could be rapidly deployed across the APS.

Copilot is already available within many APS agencies. The applications are incorporated into daily workflows and staff have existing competency in them. The government’s existing Volume Sourcing Agreement (VSA) with Microsoft also enabled agencies to quickly and easily procure and administer licences.

Copilot created a secure and guard railed environment for APS staff to experiment with generative AI.

Microsoft Graph ensured compliance with existing Copilot permission groups, allowing APS staff to familiarise themselves with generative AI in a controlled setting.

Although these characteristics made Copilot an understandable choice for the trial, there are limitations of it as a proxy. Other available generative AI tools possess some similar traits, but the compressed timelines of the trial dictated a solution that could be procured and deployed with confidence that it would be operational and secure within the trial timeframes.

A.2 Trial administration

Licensing arrangements

The DTA utilised the existing Microsoft VSA to administer the trial, in coordination with Data3, the License Service Provider (LSP) for that arrangement. Agencies purchased licenses through the DTA using a central enrolment that was established for the purpose of the trial only.

Governance

The trial was governed by a Program Board, chaired by the DTA and consisting of voting members representing the following 14 agencies across the Australian Government:

- Australian Digital Health Agency

- Australian Public Service Commission

- Australian Taxation Office

- Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

- Department of Employment and Workplace Relations

- Department of Finance

- Department of Health & Aged Care

- Department of Home Affairs

- Department of Industry, Science and Resources

- Digital Transformation Agency

- IP Australia

- National Disability Insurance Agency

- Services Australia

- Treasury.

The Program Board reported to the AI Steering Committee (the governing body of the AI in Government work which reports to the Secretaries’ Board Future of Work sub-committee, and the Secretaries Digital and Data Committee) which provided operational oversight, monitoring and reporting, and escalation of issues outside the scope of the trial, as well as endorsing other key operational decisions. The Program Board was not responsible for reviewing or endorsing its evaluation, but where appropriate visibility was provided to voting members only. The evaluation of the Trial including the evaluation plan, content of participation surveys and the final reports were directly considered and endorsed by the AI Steering Committee.

Microsoft were invited to attend Program Board meetings as an observer and to update members on progress, such as their response to addressing issues raised through the central issues registers, and product roadmap updates. Before finalising the terms of reference for the Program Board, the DTA sought external probity advice to ensure there were no perceived or actual conflicts of interest in Microsoft’s participation.

A.3 Overview of the evaluation

The evaluation assessed the use, benefits, risks and unintended outcomes of Copilot in the APS during the trial.

The DTA engaged Nous to conduct an evaluation of the trial based on 4 evaluation objectives designed by the DTA, in consultation with:

- the AI in Government Taskforce

- the Australian Centre for Evaluation (ACE)

- advisors from across the APS designed 4 evaluation objectives.

Employee-related outcomes

Evaluate APS staff sentiment about the use of Copilot, including:

- staff satisfaction

- innovation opportunities

- confidence in the use of Copilot

- ease of integration into workflow.

Productivity

Determine if Copilot, as an example of generative AI, benefits APS productivity in terms of:

- efficiency

- output quality

- process improvements

- agency ability to deliver on priorities.

Adoption of AI

Determine whether and to what extent Copilot, as an example of generative AI:

- can be implemented in a safe and responsible way across government

- poses benefits and challenges in the short and longer term

- faces barriers to innovation that may require changes to how the APS delivers on its work.

Unintended consequences

Identify and understand unintended benefits, consequences, or challenges of implementing Copilot, as an example of generative AI, and the implications on adoption of generative AI in the APS.

B.1 Overview of the evaluation methodology

The evaluation has been jointly delivered by the DTA and Nous.

A mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate the trial against the 4 trial evaluation objectives. Working with the Australian Centre for Evaluation, DTA designed the evaluation plan and data collection methodology with the pre-use and post-use survey. Nous reviewed and finalised the evaluation plan and assisted with the remaining evaluation activities. Specifically, these included:

- conducting focus groups with trial participants,

- interviewing key government agencies,

- co-designing the post-use survey with the AI in Government Taskforce,

- delivering the post-use survey.

The engagement activities led by Nous complemented engagement conducted by the DTA earlier in the year. Table 8 below details the key activities and milestones of the trial and evaluation.

| Start date | End date | Description | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | |||

| 7 August | - | AI in Government Taskforce is established | - |

| 1 November | - | Microsoft 365 Copilot becomes generally available | - |

| 16 November | - | Trial of Microsoft 365 Copilot is announced | - |

| 2024 | |||

| 1 January | 30 June | Microsoft 365 Copilot trial period | - |

| January | February | Develop evaluation plan | DTA |

| 29 February | 11 April | Issue pre-use survey | DTA |

| 29 February | 19 July | Collate items into issues register | DTA |

| 7 March | 13 May | Interview DTA trial participants | DTA |

| 3 May | 17 May | Issue pulse survey | DTA |

| 13 May | 20 May | Analyse surveys and DTA trial participant interviews | Nous Group |

| 13 May | 24 May | Develop mid-trial review and interim report | Nous Group |

| 24 June | 19 July | Conduct focus groups | Nous Group |

| 2 July | 12 July | Issue post-use survey | DTA |

| 8 July | 20 July | Analyse qualitative and quantitative data analysed | Nous Group |

| 8 July | 24 August | Develop final evaluation report | Nous Group |

| 19 July | 26 July | Review agency reports | Nous Group |

A program logic outlined the intended impacts of the trial.

A theory of change and program logic was developed by the DTA Copilot trial team in consultation with the Australian Centre for Evaluation.

A theory of change describes, at a high level, how program activities will lead to the program’s intended outcomes. The following program logic expands on the theory of change, articulating in more detail the relationship between desired outcomes and the required inputs, activities and outputs.

Inputs

The foundation of the framework consists of inputs, which include:

- staff time and resources

- expenditure

- copilot licences

- Microsoft contract.

Activities

The activities build upon the inputs and are designed to facilitate the use of Copilot:

- Establishing groups in government teams to share experience and learnings with Copilot.

- Establishing Copilot leads in each agency to ensure safe and responsible guidance is shared with users.

- Microsoft providing training sessions on how to use Copilot.

- Microsoft providing access to additional resources (guides and tutorials) and support to address issues.

- Establishing an issues register to collect issues on benefits challenges and barriers to innovation.

Outputs

Outputs are the immediate results of these activities:

- Staff/users are appropriately trained to engage with Copilot.

- Copilot is regularly accessed by staff/users.

- Sentiment is baselined amongst staff/users.

- Ease of use is baselined among staff/users.

- Issues register is actively populated.

Short-term outcomes

These are the direct effects of the outputs in the short term:

- Staff/users have increased confidence in the use of Copilot.

- Improvements to productivity from regular access and use.

- Improved sentiment reported from regular access.

- Unintended outcomes are identified and catalogued.

Medium-term outcomes

The medium-term outcomes reflect the sustained impact of the short-term outcomes:

- Consistent use of Copilot in day-to-day work as an embedded capability.

- Expectations of staff/users are met.

- Treatment actions are scoped for the catalogued unintended outcomes.

Long-term outcomes

The ultimate goals of the framework are the long-term outcomes:

- Improved understanding of Copilot and its safe use.

- More time available for higher priority work.

- Increased staff satisfaction.

- Unintended Copilot outcomes and challenges identified and mitigated.

Key evaluation questions guided data collection and analysis.

Nous developed key evaluation questions to structure the data collection and analysis. The key evaluation questions at Table 9 are based on the 4 evaluation objectives and informed the design of focus groups, the post-use survey and final evaluation report.

| Evaluation objective | Key lines of enquiry | |

|---|---|---|

| Employee related outcomes | Determine whether Microsoft 365 Copilot, as an example of generative AI, benefits APS productivity in terms of efficiency, output quality, process improvements and agency ability to deliver on priorities. | What are the perceived effects of Copilot on APS employees? |

| Productivity | Evaluate APS staff sentiment about the use of Copilot. | What are the perceived productivity benefits of Copilot? |

| Whole-of-government adoption of generative AI | Determine whether and to what extent Microsoft 365 Copilot as an example of generative AI can be implemented in a safe and responsible way across government. | What are the identified adoption challenges of Copilot, as an example of generative AI, in the APS in the short and long term? |

| Unintended outcomes | Identify and understand unintended benefits, consequences, or challenges of implementing Microsoft 365 Copilot, as an example of generative AI, and the implications on adoption of generative AI in the APS. | Are there any perceived unintended outcomes from the adoption of Copilot? Are there broader generative AI effects on the APS? |

B.2 Data collection and analysis approach

A mixed-methods evaluation approach was adopted to assess the perceived impact of Copilot and to understand participant experiences.

A mixed-methods approach – blending quantitative and qualitative data sources – was used to assess the effect of Copilot on the APS during the trial. Quantitative data identified trends on the usage and sentiment of Copilot, while qualitative data provided context and depth to the insights. Three key streams of data collection were conducted:

Document and data review

This involved analysis of existing data such as the Copilot issues register, existing agency feedback, agency-produced documentation e.g. agency Copilot evaluations and research papers.

Consultations

Delivery of focus groups with trial participants and interviews with select government agencies. Insights from DTA interview with participants were also incorporated into the evaluation.

Surveys

Analysis of the pre-use and pulse survey in addition to the design and delivery of a post-use survey.

At least 2,000 individuals, representing more than 50 agencies, contributed to the evaluation through one or more of these methods. Both the participation in the trial and in the evaluation were non-randomised; participants self-nominated to be part of the trial or were identified by their agencies. Efforts were made across the APS to ensure trial participants were representative of the broader APS and a range of experience with generative AI were selected. Further detail on each data stream is provided below.

Document and data review

The evaluation drew on existing documentation prepared by the DTA and participating agencies to supplement findings. DTA and agency research data was used to test and validate insights from the overall evaluation, as well as incorporate the perspective of agencies that had limited participation in the trial. The document and data review can be separated into:

Issues register

Document for participating agencies to submit technical issues and capability limitations of Copilot to the DTA.

Research papers

Documents produced by government entities that investigate the implications of Copilot and generative AI. This included: Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner’s Public statement on the use of Copilot for Microsoft 365 in the Victorian public sector; and the Productivity Commission’s Making the most of the AI opportunity: productivity, regulation and data access.

Internal evaluations

Agency-led evaluations and benefits realisation reports made available to the evaluation team. Agencies that provided their internal results included: Australian Taxation Office (ATO); Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO); Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs); Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR).

Consultations

The evaluation gathered qualitative data on the experience of trial participants through both outreach interviews conducted by the DTA and further focus groups and interviews led by Nous. In total, the evaluation has conducted:

- 17 focus groups across APS job families

- 24 targeted participant interviews conducted by the DTA

- 9 interviews with select government agencies.

Nous’ proprietary generative AI tools were used to process transcripts from interviews and focus groups to identify potential themes and biases in the synthesis of focus group insights. Generative AI supported Nous’s human-led identification of findings against the evaluation’s key lines of enquiry.

Surveys

Three surveys were deployed to trial participants to gather quantitative data about the sentiment and effect of Copilot. A total of 3 surveys were deployed during the trial. There were 1,556 and 1,159 survey responses for the pre-use and pulse survey respectively. In comparison, the post-use survey had 831 responses.

Despite the lower number of total responses in the post-use survey, the sample size was sufficient to ensure 95% confidence intervals (at the overall level) and were within a margin of error of 5%. It is likely agency fatigue with Microsoft 365 Copilot evaluation activities, in conjunction with a shorter survey window, contributed to the lower responses for the post-use survey.

There were 3 questions asked in post-use survey that were originally included in either the pre-use or pulse survey. These questions were repeated to compare responses of trial participants before and after the survey and measure the change in sentiment. These questions were:

Pre-use survey

Which of the following best describes your sentiment about Copilot after having used it?

Pre-use survey

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements: ‘I believe Copilot will…’ / ‘using Copilot has…’

Pulse survey

How little or how much do you agree with the following statement: ‘I feel confident in my skills and abilities to use Copilot.’

The survey responses of trial participants who completed the pre-use and post-use survey and pulse and post-use survey were analysed to assess the change in sentiment over the course of the trial.

Analysis of survey responses have been aggregated to ensure statistical robustness. The following APS job families have been aggregated as shown in Table 10.

| Group | Job families |

|---|---|

| Corporate | Accounting and Finance Administration Communications and Marketing Human Resources Information and Knowledge Management Legal and Parliamentary |

| ICT and Digital Solutions | ICT and Digital Solutions |

| Policy and Program Management | Policy Portfolio, Program and Project Management Service Delivery |

| Technical | Compliance and Regulation Data and Research Engineering and Technical Intelligence Science and Health |

Post-use responses from Trades and Labour, and Monitoring and Audit were excluded from job family-level reporting as their sample size was less than 10. Their responses were still included in aggregate findings. For APS classifications, APS 3-6 have been aggregated.

B.3 Limitations

The representation from APS classifications and job families in engagement activities may not be reflective of the broader APS population.

Given the non-randomised recruitment of trial participants, there is likely an element of selection bias in the results of the evaluation. While the DTA encouraged agencies to distribute Copilot licenses across different APS classifications and job families to mitigate against selection bias, the sample of participants in the trial – and consequently those who contributed to surveys, focus groups and interviews – may not reflect the overall sentiments of the APS.

For APS classifications, there is an overrepresentation of EL1s, EL2s and SES in survey activities. Conversely, there was a lower representation of junior APS classifications (APS 1 to 4) when compared with the proportions of the overall APS workforce. This means that the evaluation results may not be truly capture junior APS views (likely graduates) and disproportionately contain the views of ‘middle managers.’ In addition, the sentiments (in addition to use cases) of APS job families such as Service Delivery may not be adequately captured in the evaluation.

For APS job families, ICT and Digital Solutions and Policy were the 2 most overrepresented in survey responses versus their normal proportion in the APS. Service Delivery was the only job family that had significant underrepresentation in the surveys, comprising only around 5% of the survey responses but represent around 25% of the APS workforce.

Appendix D provides a detailed breakdown of pre-use and post-use survey participation by APS classifications and job families compared to the entire APS population.

There is likely a positive bias sentiment amongst trial participants.

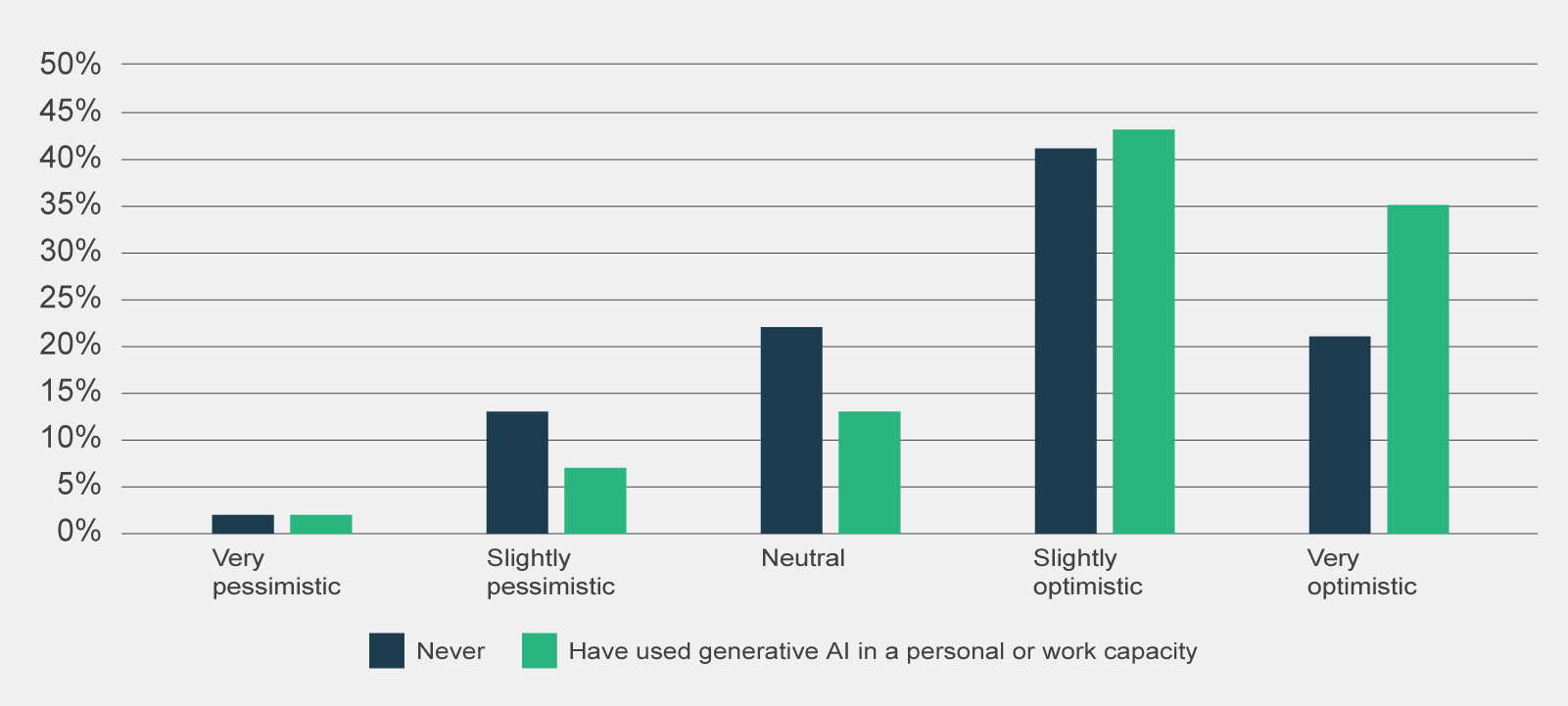

It is likely that trial participants and as a subset, participants in surveys and focus groups, have a positive biased sentiment towards Copilot compared to the broader APS. As shown in Figure 16, the majority of pre-use survey respondents were optimistic about Copilot heading into the trial (73%) and were familiar with generative AI before the Trial (66%).

Data table for figure 16

Pre-use survey responses to 'Which of the following best describes your sentiment about using Copilot?', by prior experience with generative AI (n=1,386).

| Experience with generative AI | Very pessimistic | Slightly pessimistic | Neutral | Slightly optimistic | Very optimistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | 2% | 13% | 22% | 41% | 21% |

| Have used generative AI in a personal or work capacity | 2% | 7% | 13% | 43% | 35% |

Totals may amount to less or more than 100% due to rounding.

OffThere was an inconsistent rollout of Copilot across agencies.

The experience and sentiment of trial participants may be affected by when their agency began participating in the trial and what version of Copilot their agency provided.

On the former, agencies received their Copilot licences between 1 January to 1 April 2024. Some agencies opted to distribute Copilot licences to participants later in this period once internal security assessments were complete. This meant that agencies participating in the trial had different timeframes to build capability and identify Copilot use cases, which could potentially affect participants’ overall sentiment and experience with Copilot.

Further, agencies who joined the trial later may not have been able to contribute to early evaluation activities, such as the pre-use survey or initial interviews, therefore excluding their perspective and preventing later comparison of outcomes.

On the latter, since the trial began, Microsoft has released 60 updates for Copilot to enable new features – including rectifying early technical glitches. Due to either information security requirements or a misalignment between agency update schedules, the new features of Copilot may have been inconsistently adopted across participating agencies or at times, not at all.

This means that there could be significant variability with Copilot functionality across trial participants and it is difficult for the evaluation to discern the extent to which participant sentiments are due to specific agency settings or Copilot itself.

Trial participants expressed a level of evaluation fatigue.

Agencies were encouraged to undertake their own evaluations to ensure the future adoption of Copilot or generative AI reflected their agency’s needs. Many participating agencies conducted internal evaluations of Copilot that involved surveys, interviews and productivity studies.

Decreasing rates of evaluation activity participation over the trial indicates that trial participants may have become fatigued from evaluation activities. The survey response rate progressively decreased across the pre-use to pulse to post-use surveys. Lower response rates in the post-use survey (n = 831) and for those who completed both the pre-use and post-use survey (n = 330) may impact how representative the data is of the trial population. Participation in the Nous-facilitated focus groups and the post-use survey was impacted by these parallel initiatives and the subsequent evaluation fatigue.

This means that the evaluation may not have been able to engage with a wide range of trial participants with a proportion of trial participants opting to only provide responses to their own agency evaluation. This may have been mitigated to a degree with some agencies sharing their results to the evaluation.

The impact of Copilot relied on trial participants’ self-assessment of productivity benefits.

The evaluation methodology relies on the trial participants’ self-assessed impacts of Copilot which may naturally under or overestimate impacts – particularly time savings. Where possible, the evaluation has compared its productivity findings against other APS agency evaluations and external research to verify the productivity savings put forth by trial participants.

Nevertheless, there is a risk that the impact of Copilot – in particular the productivity estimates from Copilot use, may not accurately reflect Copilot’s actual productivity impacts.

2.1 Problem definition

Clearly and concisely identify the problem you are trying to solve. Use 100 words or less.

2.2 AI use case purpose

Clearly and concisely describe the purpose of your use of AI, focusing on how it will address the problem you have identified. Use 200 words or less.

2.3 Non-AI alternatives

Briefly outline nonAI alternatives that could address this problem. Use 100 words or less.

2.4 Identifying stakeholders

Identify stakeholder groups that may be affected by the AI use case and briefly describe how they may be affected, whether positively or negatively. This will guide your consideration of expected benefits and potential risks in this assessment.

Consider holding a brainstorm or workshop to help identify affected stakeholders and how they may be affected. A discussion prompt is provided in the guidance document.

2.5 Expected benefits

Considering the stakeholders identified in the previous question, identify the expected benefits of the AI use case. This should be supported by quantitative and/or qualitative analysis.

Qualitative analysis should consider whether there is an expected positive outcome and whether AI is a good fit to accomplish the relevant task, particularly compared to nonAI alternatives identified. Benefits may include gaining new insights or data.

Consult the guidance document for resources to assist you. Aim for 300 words or less.

The Pilot Australian Government artificial intelligence (AI) assurance framework (the framework) guides Australian Government agencies through impact assessment of AI use cases against Australia's AI Ethics Principles. It is intended to complement and strengthen – not duplicate – existing frameworks, legislation and practices that touch on government’s use of AI.

The draft framework should be read and applied alongside the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government and existing frameworks and laws to ensure agencies are meeting all their current obligations. Above all, Australian Government agencies must ensure their use of AI is lawful, constitutional and consistent with Australia’s human rights obligations and reflect this in the planning, design and implementation of AI use cases from the outset.

Assurance is an essential part of the broader governance of government AI use. In June 2024, the Australian Government and all state and territory governments endorsed the National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence. The national framework establishes a nationally consistent, principles-based approach to AI assurance, that places the rights, wellbeing and interests of people first. By committing to these principles, governments are seeking to secure public confidence and trust that their use of AI is safe and responsible.

This pilot assurance framework is exploring mechanisms to support Australian Government implementation of these nationally agreed principles. Evidence gathered through the pilot will inform the DTA’s recommendations to government on future AI assurance mechanisms, as part of next steps for the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government.

The framework will continue to evolve over time. Please email the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) at aistandards@dta.gov.au if you have any questions regarding the framework.

AI use cases covered by the framework

For the purposes of the framework, agencies should apply the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) definition of AI:

Digital and ICT Investment Oversight Framework

The Whole-of-Government Digital and ICT Investment Oversight Framework (IOF) provides a way for the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) to support the Australian Government to manage its digital and information and communications technology (ICT) enabled investments. The IOF applies from early planning through to project delivery and realisation of planned benefits.

What is the IOF

The IOF is a 6 state, end-to-end framework providing a way for the government to manage digital investments across the entire project lifecycle.

Agencies developing, bringing forward or implementing digital and ICT-enabled investments are subject to the requirements of the IOF.

The six states of the IOF

Defines the strategic direction for the government’s digital delivery and future objectives and identifies capability gaps through an integrated view of…

Prioritises and advises on investments that align to the strategic direction.

Assesses whether proposals are robust and meet whole-of-government digital and ICT policies and standards prior to government consideration.

Provides assurance to government that projects are on-track to deliver expected benefits.

Provides strategic sourcing advice and ensures the government has access to value for money digital and ICT-enabled procurement arrangements.

Underpins effective decision making by providing information and analysis on the operations of the Australian Government’s digital and ICT landscape.

Defines the strategic direction for the government’s digital delivery and future objectives and identifies capability gaps through an integrated view of…

Prioritises and advises on investments that align to the strategic direction.

Assesses whether proposals are robust and meet whole-of-government digital and ICT policies and standards prior to government consideration.

Provides assurance to government that projects are on-track to deliver expected benefits.

Provides strategic sourcing advice and ensures the government has access to value for money digital and ICT-enabled procurement arrangements.

Underpins effective decision making by providing information and analysis on the operations of the Australian Government’s digital and ICT landscape.

Proposing new digital and ICT investments

Agencies must consult the DTA at the earliest opportunity when developing digital and ICT-enabled investment proposals to seek advice on alignment with the Government’s digital and ICT policies and best practice. Please note that entities must provide the DTA with all necessary information at least 6 working days prior to the release of Exposure Draft, lodgement of short form paper, or submission to the Prime Minister. For proposals subject to the IIAP, this generally requires entities to provide the DTA with draft business cases at least 7 weeks prior to Cabinet consideration. This includes the ICT Investment Approval Process (IIAP).

If your agency is planning or delivering a digital or ICT-enabled investment, you will be required to meet mandatory assurance requirements to secure confidence in delivery. These requirements are detailed in the Assurance Framework for digital investments.

The Department of Finance is responsible for providing guidance on budget processes and for agreeing to policy costings. Agencies retain responsibility for delivering digital and ICT-enabled projects.

Investments subject to the Framework

The IOF applies, in principle, to all government digital and ICT-enabled investments that meet the below eligibility criteria.

A digital and ICT-enabled investment is an investment that uses technology as the primary lever for achieving expected outcomes and benefits. This includes investments which are:

- transforming the way people and businesses interact with the Australian Government

- improving the efficiency and effectiveness of Australian Government operations, including through automation.

The IOF applies where the digital and ICT-enabled investment:

- is brought forward by a non-corporate Commonwealth entity and, where specifically requested by the Minister responsible for the Digital Transformation Agency, a Corporate Commonwealth entity

- involves ICT costs*

- is being brought forward for government consideration as a new policy proposal**.

* note – for the ICT Investment Approval Process, the annual prioritisation process and reporting purposes, only investments with initial ICT set-up capital costs of $10 million or more, or whole-of-initiative costs of $30 million or more, will be considered at these states of the Framework.

** note – The DTA and the Department of Defence are applying the IOF in a way that avoids duplicating Defence’s established, comparable and effective strategic planning and decision-making process under the Defence Integrated Investment Program (IIP) or the application of standards and policies compromising warfighting or coalition requirements. The Office of National Intelligence is also tailoring the IOF by using existing policies and governance processes already in place in the National Intelligence Community to lead the provision of advice to the Australian Government for Top Secret digital and ICT-enabled proposals across the life cycle, including assurance, for Top Secret proposals seeking funding outside the Defence IIP process.

Off